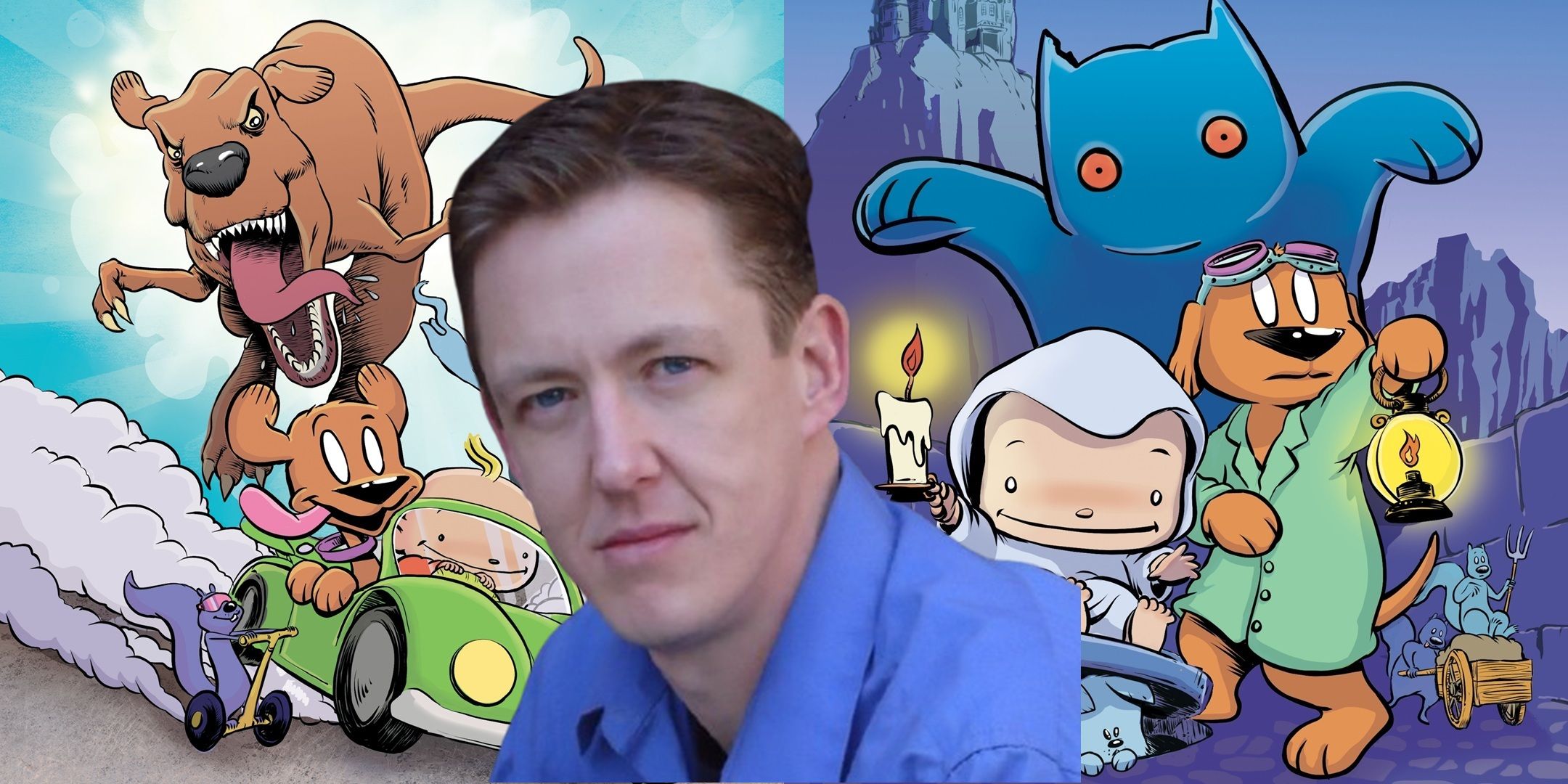

In 2004, Brian Anderson launched the webcomic, Dog Eat Doug, which moved into newspaper syndication in 2005. The comic was initially about the relationship between Sophie, the “dog” of the title (based on Anderson's real life dog, Sophie), and her new baby “brother,” Doug. Over the years, the strip has expanded to include Anderson's other pets, including his family's cats and other foster animals.

Anderson recently expanded into the world of graphic novels with a series of graphic novels essentially adapting the comic strip into graphic novel form from the children's publishing company, Marble Press. The first two were released in October, Sophie: Jurassic Bark and Sophie: Frankenstein's Hound. CBR talked to Anderson about the series, and Anderson's history with comics and comic BOOKS!

Related

Patrick McDonnell on Mutts' 30th Anniversary, Plus Finally Breaking Guard Dog's Chain

Award-winning cartoonist Patrick McDonnell spoke with CBR about Mutts' 30th anniversary, and the release of his new Mutts book, Breaking the Chain

CBR: I think people sometimes forget just how important book versions of comic strips were on many people growing up. This all started, of course, with Pogo in 1951, where its affordable reprint collections became the framework that every other strip followed in the 1950s and 1960s, most famously with Peanuts a couple of years later (when the strip was still in its earliest form). What was the first book collection of comic strips that you remember reading as a kid?

Brian Anderson: You’ve obviously seen my bookshelf. I am lucky enough to have my dad’s comic collection from the 1950s. That included the first Peanuts and Pogo collections. Both are next to my drawing table right now. They had a profound effect, not just on my art, but on how I viewed what was possible with comics. I encourage everyone to read the first few years of Peanuts. It is dramatically different from what most of us first encountered in the papers. It was darker, dare I say a bit goth. That underlying depression in Charlie Brown was much more pronounced, and yet it captures your heart.

I did not realize it as a kid, but reading those early Peanuts strips taught me that comics were so much more than just set-up, punchline gags. Comics can have true emotional depth which I think makes the laughter stronger.

Obviously, now that you're moving into the graphic novel field, I was wondering the same thing about what was the first graphic novel (and/or serialized comic book) that really blew your mind as to the possibilities of that form of media back in the day?

There were so many. In second grade, my cousin in Ireland introduced me to 2000 AD. I had never seen anything like it! The next epiphany happened in the eighth grade. I walked into That’s Entertainment in Worcester, Mass, and picked up a copy of “Sandman”. My days of reading superhero books were over (except Batman. I’m never giving up Batman).

While there are obviously some outliers, most notable comic strip creators typically had some form of OTHER comic strip pitches/ideas BEFORE their big one. Was that that case for you with Dog Eat Doug? If so, was it just a matter of the other strips not being something you wanted to devote years of your life to?

That’s exactly it! I was developing two other strips for a syndicate, and I could not picture doing either for ten years. Sophie had just joined our family and one day while penciling away in a Charlie Brown stupor I took a break to play with her. The entire concept popped into my head while we played chase in the backyard. I launched the strip online two months later and the following year it was syndicated in papers.

The comic strip format, of course, is designed that each strip stands on its own, even the ones that tell overarching stories (which is why reading collections of, say, Amazing Spider-Man strips, is always kind of off-putting, almost like how old school comic books sometimes read oddly in trade paperbacks, since every “chapter” has a recap, which is unusual when you read them sequentially). How long did it take you to fully get your mind to “break free” from those constraints when adapting Sophie and Doug to the graphic novel format?

I collect old superhero and action comic strips, so I know what you’re talking about. In the daily strip I worked hard so that each strip would make you smile or sometimes feel sad, but I also worked in longer story arcs like Indiana Bones, the Canine Crusader and, eventually, my foster dogs. Switching to graphic novels was freeing in that I got to let the character loose and give them a vast playground. But shaking the four panel rhythm was tricky. It helped to have a stellar editor who got Sophie’s personality. And also having a team at Marble Press who assisted me in the transition.

I plan out Sophie’s growth and development through each book. I know who she is at the beginning and the end. Then I brainstorm all the fun, crazy ideas and see how they can fit along her path. In other words I do a lot more outlining before sitting down and laying out the books.

The graphic novel format is how I always envisioned the characters. That was hard to do when you had to write 365 strips a year. You probably noticed the first book had that comic strip rhythm in the beginning. Like many things, you learn by doing.

How did you go about determining how much of the graphic novels would be set in different “timelines” of the strip? The cats didn't show up until seven years in, but they're here by the end of the first graphic novel, you got to the foster stories in the second book, and even the imagination stuff shows up very quickly in the first graphic novel, when it took a while longer to really show up in the strip. Do you think there is sort of a “peak” era of the strip that you wanted to get to as soon as possible (sort of like how Charles Schulz, after those early Peanuts collections, essentially “banned” those early strips from being reprinted again for decades, as he wanted to concentrate on only reprinting the “classic” era of Peanuts, circa 1966-forward…with that tightening to 1974-forward later on, basically post-Peppermint Patty's introduction)?

Yes, that’s exactly how I went about it. A comic strip takes a long time to find your footing. That’s why I tell younger artists to write 60-100 strips and throw them out. That helps get rid of the “easy” jokes and gives you time to get to know your characters. I struggled in the early days of the strip to find the tone and the style of the comic.

The graphic novels gave me the chance to re-launch Sophie as I had always dreamed it in my head. I wanted it to be new and exciting for longtime readers of the newspaper strip. My real life animals showed up in the newspaper comics when they came into our real lives. I also had the advantage of drawing and writing these characters for years which allowed me to focus more on creating longer, more robust storylines. Having characters with fully formed personalities is a lot more fun than struggling to figure out who they are. In the graphic novels for example, I knew from the jump that the cats were crazy, quantum physicists bent on taking over. I don’t have to experiment with their goals or how they go about accomplishing (or failing) at them. That made it a simple choice to have them interrupt the first graphic novel and talk directly to the reader. I really wish the old Peanuts strips had stayed in print. I think so many people would have a deeper appreciation for the beloved characters. With “Sophie”, I love that new readers can go back and read the old comics. I think it connects them more to the characters.

One of the things that strikes me about the Sophie graphic novels is how many of the references are stuff that only adults would get. Is that a goal of yours, to give adults their own special take on the books, as well?

Yes. Sophie took on a lot of my traits in the newspaper strips. She also sat with me on the couch to watch Doctor Who. So I always slipped in little Easter eggs here and there. The graphic novels gave me the opportunity to do more than hide little Addams Family figurines or a Tardis in the pages. I could take the Pixar approach and sneak in humor for the parents too. I’ve always wanted Sophie to be something parents wanted to read with their kids. And now I hear from parents who first read Dog Eat Doug in papers reading the Sophie books and loving them as much as their kids do. That means the world to me.

Related

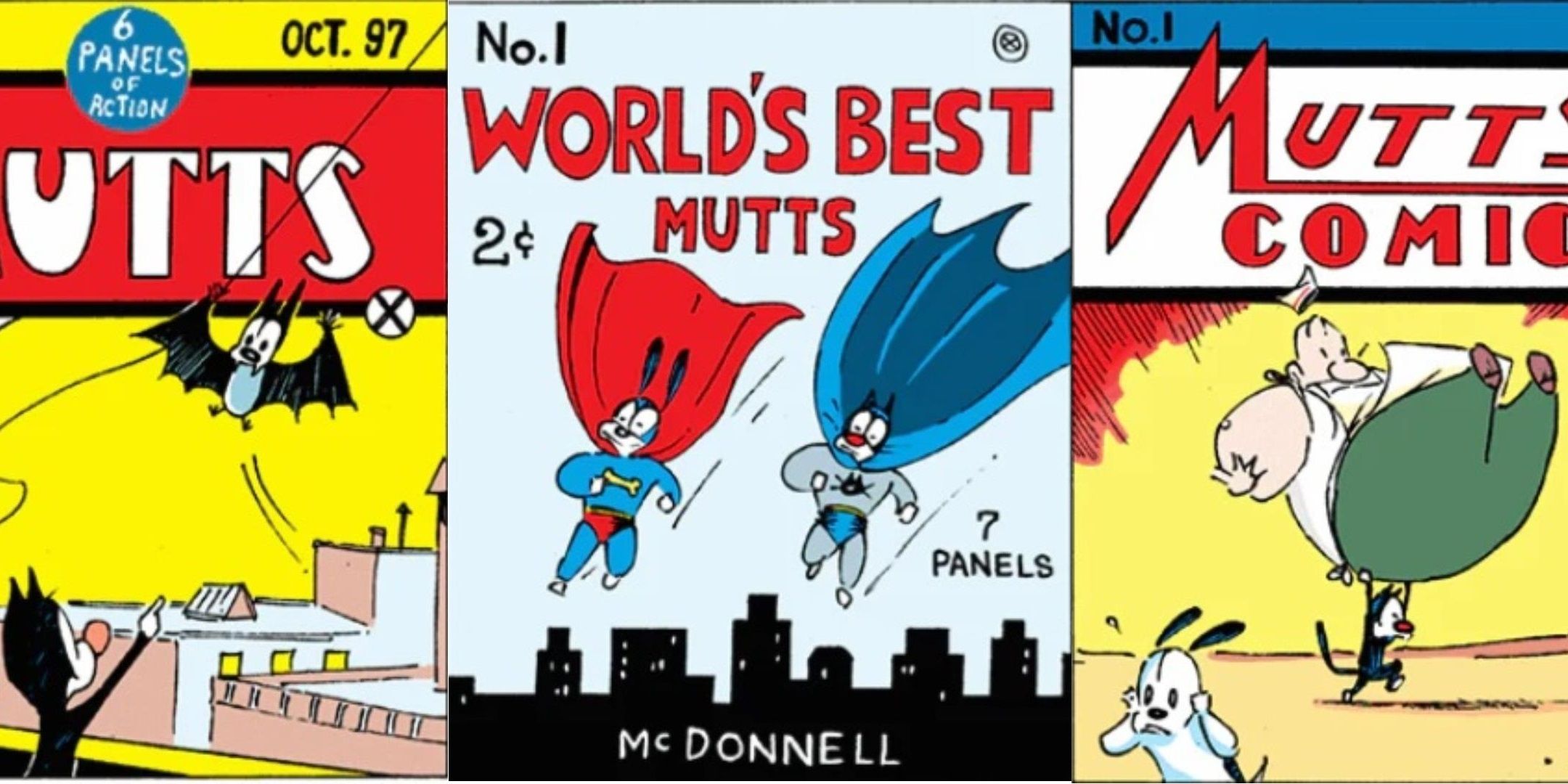

Mutts' Classic Comic Book Cover Homages

Patrick McDonnell often pays tribute to classic comic book covers in his iconic hit comic strip, Mutts, and here we share a few examples

When it comes to an imagination storyline, do you come up with the imagination hook first (like “Oh, an Indiana Jones riff would be fun – Indiana Bones!”) and think of what real life behavior would work for something like that, or is it the real life behavior that makes you think “Oh, that's like Indiana Jones…”?

It’s a bit of both. The Indiana Jones storylines sprouted from the rivalry between Doug and Sophie. The Batman parodies came from my obsession with the caped crusader and the fact that Sophie truly was a superhero to my son. The foster dog stories are based on actual dogs that have come through my home. Those are trickier, as I’ve worked with a lot of troubled dogs. I never wanted to get heavy-handed preaching “adopt don’t shop”. In real life my dogs treated the troubled fosters with such care and compassion I knew I wanted that to come out in the books. But it also has to be funny.

In the upcoming book 3, I wrote about a foster who had severe anxiety and human fear issues. It was a heartbreaking situation, and I wasn't sure if it would work in the comics. Really, all I did was create the cartoon version of Luna and drop her in front of the cartoon versions of Annie and Sophie. Their personalities did the rest. And that’s also the reason I put in the real life photos at the beginning of the book.

One of the truisms of comic strip creation is that comic strip creators are very much an island (unless they have a studio, of course). So what was the transition like to working much more closely with an editor, like you do in the graphic novel process?

It was a welcome one. Becoming an island is not something you think about or are prepared for when you start out. There are days when you forget that people actually read the strip! You can get lost in a self-doubting mind loop. Having an editorial team to work with and bounce ideas off of is a godsend. I was very fortunate to find a publisher who didn’t want to throw Sophie out there and see if it sticks but wanted to be on board for the long haul and build something special. That’s not something I had at the syndicate.

I was talking to Patrick McDonnell recently about Mutts, and he noted that when you write a series for a long enough, you suddenly find yourself almost led by the characters, like rather than fitting them into the plot, the plot has to fit around them. Have you found the same to be true in your work?

I loooove Mutts! The elegant simplicity of his art is the hardest thing to do in cartooning. Patrick is a master! And yes, after you do it for a longtime, the characters take over. You sit down to write a simple cute story about walking Sophie through a local park, but she’d rather fight a horde of ninja socks. You learn to let go, sit back and watch what happens.

Since you draw from real life all of the time, what's the most unusual real life thing that you can recall that inspired a comic plot?

A lot of them. And some real life things were too graphic for the comics. The diaper on the ceiling came from real life, although I cleaned it up a lot for the strip. Most of Sophie’s encounters with wildlife came from the real world. I was walking my son and Sophie around the block and a fox exploded from the woods and almost ran into the stroller. A nuclear blast of rage came out of Sophie, and she almost dragged me and the stroller into the woods.

“The Demon Cat of Georgia” story was inspired by a trip to the family farm. Our relatives fed the feral cats so there were a bunch hanging around. Sophie loved cats so no issues until this one cat showed up. Needless to say he didn’t like dogs. Sophie hid in the car anytime that cat was prowling the yard. After Sophie passed I wasn’t sure I’d continue the strip. Then I realized that the comics were how I held on to her spirit. So much of the inspiration comes from my other dogs and cats now.

There's so many superhero references in the series (like Sophie's Bat-Lab character). Would you ever want to write a traditional superhero story?

Absolutely. I’m pitching one right now. It’s a far cry from Sophie’s talking cupcakes world but it’s a story worth telling. The story is based on a K-9 handler and we’re building a fictional, supernatural world around his experiences. Outside of that, I would love to write a Batman story. Especially one where he adopts a dog.

Sophie: Jurassic Bark and Sophie: Frankenstein's Hound are both on sale now.