By Yin Nwe Ko

Peter Pongrácz, a proud owner of four housecats — Cookie, Sushi, Crumbles, and Stinky — has an insatiable curiosity about the enigmatic inner lives of the world’s second most popular domesticated pets. In his quest to fathom their sentiments and thoughts towards humans, he grapples with the challenge of finding graduate students with the patience and determination required for this intricate research. The allure of dogs, ever-eager for human validation and a tasty bone, often diverts potential researchers. This challenge hit home during an incident at Eötvös Loránd University in Budapest in 2005, when a cat, brought into their laboratory, promptly vanished into an air conditioning duct, prompting a laborious rescue mission.

It took over a decade for Pongrácz to find a willing graduate student to reattempt cat research. Passionate about studying cats, he eagerly awaits students keen on delving into this intriguing domain. Stepping back into the realm of “cat cognition”, Pongrácz and his team decided to study cats in their natural habitats to avoid the earlier disappearing act. They queried cat owners about their feline companions, exploring various aspects of their behaviour and understanding. The subsequent observations revealed fascinating insights into feline abilities to interpret human intentions, particularly in following a person’s gaze. Notably, indoor and outdoor cats displayed distinct cognitive habits, shedding light on the impact of lifestyle on their behaviours.

This resurgence in cat research marks a departure from decades of dogs dominating the realm of animal studies within households. Pongrácz’s earlier experiments with dogs in the ‘90s and early 2000s fuelled the current renaissance in cat cognition research, breathing new life into a once-neglected field despite the challenges posed by these often elusive and unpredictable feline subjects.

In the years since research laboratories have emerged globally, dedicated to delving into the intricate minds of dogs — measuring their ability to comprehend and interpret human emotions and cues, grapple with abstract concepts and social dynamics, and address fundamental inquiries regarding the human-canine relationship, notably whether dogs genuinely harbour love for us. However, during most of this period, cat enthusiasts faced a dearth of such opportunities. Recent times have witnessed the emergence of an enthusiastic cohort of cat lovers, driven by a profound allegiance to their beloved feline companions and a conviction that cats have been persistently and unjustly misunderstood. These fervent advocates have started adopting experimental models and incorporating lessons gleaned from canine studies. In this process, they are unravelling longstanding questions that have intrigued cat owners, dispelling prevailing misconceptions.

Contrary to the belief of them being solitary and aloof, contemporary understanding reveals that many cats possess the capacity for intricate social relationships and form meaningful attachments to their human caregivers. Their intelligence is more substantial than commonly assumed; they can recognize their names, and their owners’ voices and faces, interpret complex human signals, learn rules and routines, decipher basic human cues, and make conclusions based on limited information. Above all, mounting evidence indicates that the bond between humans and cats is reciprocated, genuine, and enduring. Cats, the evidence suggests, not only like us — they truly love us. Their expression of affection is simply more subtle compared to dogs, an aspect that has taken time for us to comprehend fully.

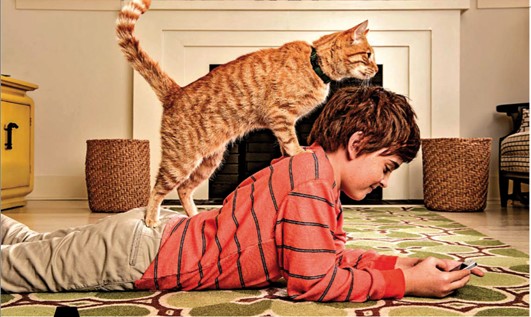

The love we hold for our dogs is readily apparent — manifested through their exuberant displays of affection, their sheer delight at our presence evident in joyful leaps, enthusiastic licking, tail-wagging, and expressive pleas for attention. On the other hand, the human-feline relationship has always been nuanced. While some cats may tolerate a gentle scratch or a few moments of attention, they often exude an air of regality and indifference to our overtures, seemingly asserting ownership over us and bestowing their attention as a favour. Instances of territorial behaviour, like peeing on the couch in our absence or their ingenious efforts to awaken us when hungry, add to this enigmatic dynamic. Yet, akin to dogs, cats have seamlessly integrated into the fabric of our domestic lives and families, showcasing an ability that warrants thorough scientific exploration.

The financial investment and emotional bond with cats are substantial, mirroring their immense appeal in modern society. In 2022, Americans allocated a staggering $136.8 billion for their pets, with a significant portion dedicated to cats. Presently, there are approximately 220 million pet cats worldwide, nearly 58.8 million of which reside in the United States alone (in comparison to roughly 471 million dogs). This enduring charisma of cats has been documented throughout human history. Archaeological finds, such as a 9,500-year-old burial site on Cyprus, reveal a human adult interred with an eight-month-old cat, likely transported to the island by ancient seafarers. Ancient Egyptians revered deities that bore both human and feline attributes, exemplifying the deep-rooted connection between humanity and cats. The feline-human relationship is a rich tapestry deserving of continued exploration and understanding.

In the sacred precinct of Bubastis, nestled in the Delta city of Bubastis, scores of mummified cats and miniature cat sculptures have been unearthed, a testament to the reverence bestowed upon the feline goddess Bastet, daughter of the Sun God. Columns adorned with cat imagery adorned this hallowed place, showcasing the ancient Egyptians’ deep-rooted belief in the mystical nature of cats. Leslie A. Lyons, a geneticist at the University of Missouri’s College of Veterinary Medicine, reveals that the intertwined history of cats and humans spans over 12,000 years. Her genetic analysis, published in the science journal Nature in November 2022, unveils the profound connection between these two species.

This extraordinary companionship began over 10,000 years ago when humans transitioned into agrarian societies in the fertile crescent between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, following the retreat of glaciers. The emergence of grain stores and refuse lured mice, attracting cats who diligently maintained the food supplies by keeping disease-carrying rodents at bay. This symbiotic relationship between humans and cats led to a distinctive bond, distinct from that with dogs. Early pet dogs had to entice humans for food scraps, evolving an ability to tug at human emotions. Cats, on the other hand, thrived by maintaining a discreet presence, independently hunting for sustenance. Their evolutionary path forged them into cautious, curious creatures, often evading danger by fleeing and hiding, an instinctual behaviour borne from their vulnerable position in the food chain.

Understanding this evolutionary trajectory allows us to grasp why cats, although more recently selectively bred by humans, have successfully become integral parts of households. Their ability to trigger our inherent parental instincts, akin to dogs, plays a pivotal role in this success. Jonathan Losos, an evolutionary biologist at Washington University, emphasizes this attribute, highlighting a study revealing that the purrs of cats, particularly in the 220-to-520 hertz frequency range, akin to a baby’s cries, engage our innate response to caregiving. Cats have subtly moulded their communication, notably their meows, deviating from their wild ancestors, further enhancing their compatibility with humans. This unique interplay of ancient history and subtle evolutionary shifts underpins the enigmatic and enduring appeal of cats as beloved pets.

Pongrácz finds the proposition intriguing, suggesting that more research is warranted to delve deeper into this idea. Cats possess a distinctive facial structure with a flat face, short nose, and prominent forward-facing eyes, resembling the features of a baby — an aspect less prevalent in most livestock, whose eyes are typically situated on the sides of their heads. An adult house cat typically weighs between 8.8 to 11 pounds, close to the average weight of a newborn baby, which is about 7.5 pounds. However, devoted cat lovers contend that this likeness is just the surface.

Kristyn Vitale, an assistant professor specializing in animal health and behaviour at Unity College in Maine, passionately argues that cats hold a prowess for earning our affection far beyond what is conventionally acknowledged. She embarked on a decade-long mission to dispel the misconceptions that label felines as inherently antisocial, untrainable, and unfriendly. Drawing from her own cherished experiences with her cats during childhood, Vitale sought to reveal the social and affectionate nature of cats. Through meticulous studies, she has substantiated that cats possess the ability to form significant attachment bonds with human owners, akin to those observed between human parents and children. This bond, cultivated during a critical developmental window, is so profound that it has left lasting genetic imprints through domestication, shaping the enduring cat-human relationship. In the wild, this window lasts about two weeks, whereas in domesticated cats, it extends to approximately two months, solidifying the foundation of their attachment to humans.

The motive driving Pongrácz and his colleagues at Eötvös Loránd University in 2005, during the now-famous air vent experiment, was to uncover a question that perplexes many cat owners daily: How much do our feline companions truly comprehend? They aimed to answer this by employing a test adapted from the realm of human and primate developmental psychology, a test designed to assess an animal’s ability to infer the location of hidden food based on human cues.

In this experiment, researchers hid food in various containers and employed cues like staring at, nodding toward, or pointing to the correct container. Success in this seemingly straightforward task denotes a profound understanding — recognizing that the person pointing intends to assist. Human infants typically develop this capacity at around four to nine months, marking a significant communicative milestone. Astonishingly, cats exhibited comparable abilities to some infants and dogs, showcasing their remarkable aptitude for this form of communication.

However, conducting this experiment posed its own set of challenges. Even in familiar home environments, cats often froze or lost interest when strangers were present, hindering smooth data collection. Yet, the outcomes revealed a fundamental truth: cats could respond effectively to human cues to locate hidden food, aligning them with dogs in this social cognitive capability. Pongrácz underscores that both cats and dogs swiftly grasp the core rules of the human household they inhabit, illustrating their adaptability and attentiveness to human interactions. Recent research continues to underline the social intelligence of cats, illustrating their capacity to recognize and respond to their owners through auditory and visual cues, affirming the intricate interplay between humans and their feline companions.

In further exploration of feline cognition, Saho Takagi from Kyoto University engaged in an experiment involving the voices of cat owners played through various speakers in a room. The feline subjects displayed surprise by looking around or twitching their ears when the voices appeared to move faster than anticipated. This behaviour suggests that cats were attentively listening and could create a mental map of their owner’s location. Remarkably, these cats also exhibited signs of jealousy, reacting more intensely to a soft-toy cat previously petted by their owner.

The contentious nature of feline-human relationships can be attributed partly to misunderstandings. Cats often respond to human approaches with indifference, fear, or aggression, fuelling the misconception that they don’t appreciate human company. Kristyn Vitale and other cat advocates argue that this could stem from communication barriers. Cats lack the facial muscles to exhibit expressions like dogs, making their signals less apparent. Unlike dogs with their highly expressive faces, cats cannot raise their eyebrows or make sad faces. This limited facial expression can confuse, as evidenced by a study where participants struggled to interpret cat facial cues accurately.

Cats, primarily solitary animals in nature, have less evolutionary pressure to develop overt signalling capabilities compared to pack-oriented dogs. Nonetheless, cats convey subtle signals, requiring an understanding of their specific cues. Insights into cat signalling have been gleaned from studies of feral cats, revealing gestures like slow blinking, mutual grooming, and rubbing cheeks — a lexicon of communication allowing them to express relaxation, friendliness, and social acceptance.

Understanding these subtle cues is vital in unravelling the complex language of feline communication and nurturing meaningful connections with our enigmatic feline companions.

When cats approach another cat with their tail held up, it’s generally a sign of peace, according to experts. They communicate largely through body language; for instance, direct eye contact is often interpreted as a threat, prompting defensive responses like hissing and making their body smaller. Despite their sometimes aloof demeanour, cats pay close attention to their owners. Research by Atsuko Saito from Sophia University in Tokyo in 2019 showed that cats can recognize their owners’ voices and respond to familiar words and even their names, though they may not understand the meaning. Cats also pick up on the intonation of human speech, particularly responding to higher-pitched, baby-like voices.

Understanding feline behaviour is essential in fostering a strong bond. While cats can appear finicky, they have distinct preferences and communication methods. Cats prefer frequent but low-intensity social interactions, similar to how they would approach captured prey in the wild. Contrary to the misconception that cats are untrainable, they can be effectively trained given the right conditions. Kristyn Vitale’s study showcased that cats respond to rewards like food, toys, preferred scents, and human interaction, demonstrating their trainability, comparable to dogs. Recognizing and respecting these nuances allows for a deeper and more meaningful relationship with our feline companions.

In 2020, Fumi Higaki, a dog trainer, highlighted the importance of understanding a cat’s boundaries during interactions. Research indicates that a positive and lasting interaction with a cat occurs when the cat initiates contact, rather than being approached by humans. Cats, being inherently in control, prefer setting the pace of social engagement, and feeling free to retreat when they desire. Additionally, cats have distinct motivations regarding food, differing from dogs. While they appreciate a good meal, providing food doesn’t automatically forge a friendship with them. Unlike dogs, cats are typically occasional grazers. Fascinating instances like an 11-year-old cat in Ichinomiya, Japan, displaying learned behaviours demonstrate the depths of feline abilities. Researchers like Pongrácz eagerly anticipate future studies comparing domesticated cats with their non-domesticated counterparts, exploring behaviours in group living situations and unravelling further mysteries of feline behaviour. In the years ahead, a promising influx of feline-loving graduate students offers hope for insightful discoveries in feline science.

Reference: Abridged from Newsweek (22.9.2023)